“I was in Xi’an visiting terracotta last week. The cultural relics and stories of archaeologists deeply fascinated me,” said Serge Haroche as he recalled his trip to China this time, “If I have not gone into physics, I think I would like to be an archaeologist.”

For 80-year-old Nobel prize-winning physicist Haroche, curiosity has always been the driving force behind his career.

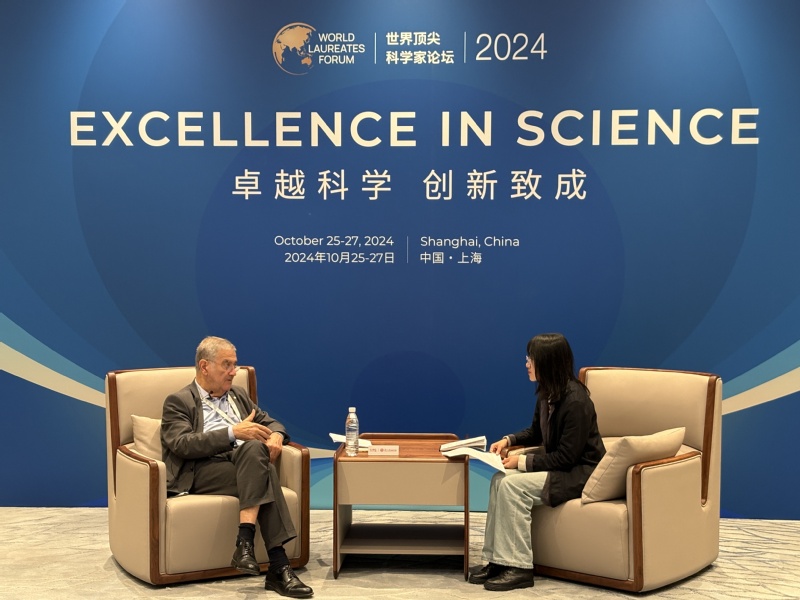

Haroche is interviewed by People’s Daily at 2024 WLA Forum. (Photo provided to People’s Daily)

A compelling game

To Haroche, scientific research is like a compelling game. Since childhood, he has had an innate obsession with numbers, measuring everything in sight - from counting tiles on walls to calculating the diagonal length of a cube.

In this way, his world turned into a marvelous funfair full of mysteries to unfold.

As a high school student back in the 1950s, Haroche witnessed the launch of mankind’s first artificial satellite. He then managed to calculate the orbital period, gravitational field, and escape velocity of its rocket. His purpose was not to achieve anything specific, but rather to satisfy his curiosity about the science behind the satellite’s journey.

“I often went to Palais de la Découverte as a young kid,” the quantum physicist recounted to the reporter with childlike enthusiasm. He described a spiral installation featuring π, saying, “It stretched on forever, with the decimal digits displayed in a beautiful, endless spiral. I wondered how the numbers could be measured so precisely.”

“It has the number π after the decimal point on its wall, which curled into a long spiral. The spiral of numbers is unrepeated, completely lack of rules. It just goes on into eternal stretching. This has thrown me into deep thoughts,” wrote Haroche in his book “I wonder how the numbers can be measured so accurately.”

“The atoms and photons in quantum physics follow some counterintuitive rules,” Haroche said. “It’s an allure that you cannot easily resist.”

Capturing Schrödinger’s Cat

After receiving his Ph.D., Haroche crossed the Atlantic to Stanford University to work as a postdoctoral fellow of Professor Arthur Schawlow.

Haroche was introduced to a lab full of possibilities and excitement by Arthur, a pioneer laser physicist at the time. Haroche spent his time there playing with a range of state-of-the-art physical tools, such as some of the world’s first tunable lasers.

Back at ENS in 1973, Haroche set up his own lab. There, he and his research team used superconducting cavities to study the long-term storage of microwave photons and manipulated photons with Rydberg atoms.

With his team, Haroche managed to observe the quantum entanglement, and finally found a way to measure the quantum without destroying it. That is to say, he successfully solved the puzzle set by Erwin Schrödinger in 1935.

The puzzle was raised to challenge theories of quantum physics by describing a cat’s impossible overlapping state of life and death. What obsessed the physicists most was the vulnerability of atoms, making them hard to detect, not to mention being used for experiments.

Haroche and his team achieved mastery over atoms and photons. They bridged the gap between quantum and classical physics through the manipulation of atoms, realizing the hope of physicists to observe the microcosm without disrupting it.

Solving the puzzle earned Haroche a Nobel Prize in physics in 2012, which he shared with American physicist David Jeffrey Wineland “for ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems.”

Haroche described himself as fortunate to have been born after the laser was invented. He said, “Laser makes it feasible to capture the atom, creating an ideal state for us to do further research with an atom that nearly stays still.”

His work has been pivotal in quantum physics, overcoming the challenge of observing and measuring the state of an atom. It has successfully addressed the unresolved question that has long surrounded Schrödinger and his enigmatic cat.

Transmission of light to infinity and beyond

In 1966, at age 20, Haroche joined the Kastler-Brossel Laboratory at ENS in Paris. This laboratory was renowned for its brilliant academic lineage. His supervisor, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, and his “grand supervisor,” Alfred Kastler, both won a Nobel Prize.

“I have been very lucky to be trained in such an environment,” Haroche said.

In October 1966, on the day Kastler was announced as a Nobel laureate, a group photo was taken at ENS’s Hertz Spectroscopy Laboratory (later renamed Kastler-Brossel Laboratory). From left to right: Franck Laloë, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, Alfred Kastler, Serge Haroche, Jean Brossel, and Alain Aspect. (Photo: The Science of Light: From Galileo’s Telescope to Quantum Physics)

As a professor, Haroche continued the lab’s tradition, engaging students and colleagues in open discussions about both successes and failures. “I hope to be as good a mentor to my students as mine were to me,” he said, spreading his hands with a bashful smile.

Asked about his experiments, Haroche often explained complex ideas in simple terms, such as comparing atoms’ behavior to “a ping-pong ball bouncing back and forth.” Through global lectures, the popular platform TikTok, and his book The Science of Light: From Galileo’s Telescope to Quantum Physics, he brought the history of humankind’s pursuit of light to diverse audiences, making the science of light accessible to all.

“Quantum optics needs exchanges,” he said, further emphasizing that the advancement of basic science relies on the relentless efforts of generations of researchers, with each discovery paving the way for future innovations.

Advocating Freedom and Trust in Science

While science progresses rapidly, Haroche has voiced concern about the public’s limited understanding of science. Speaking at the 2023 WLA Forum, he said, “If we evaluated Einstein by today’s KPIs, he might not be seen as one of the world’s greatest physicists.” Haroche stated that prioritizing short-term gains over long-term research could stifle innovation.

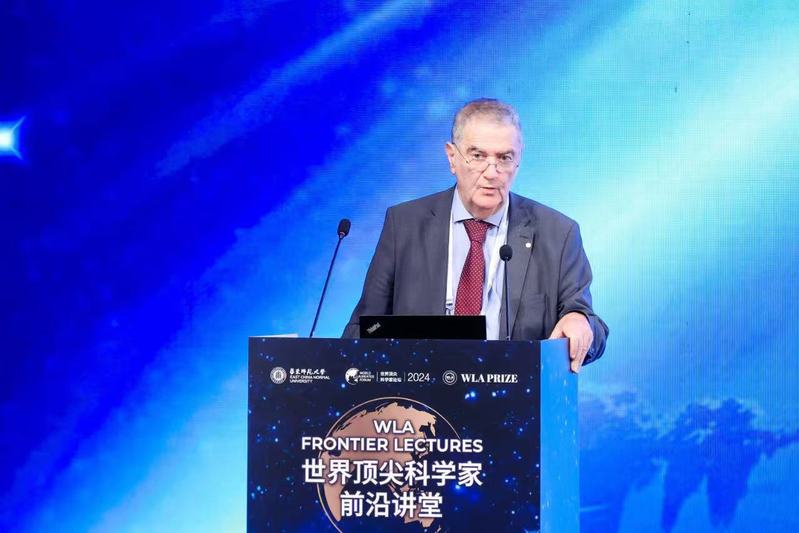

Haroche delivers a lecture at East China Normal University. (Photo: East China Normal University)

A firm advocate for “blue-sky research” - fundamental research without immediate application - Haroche said, “Scientific knowledge about the universe may be ‘useless,’ but it is vital.” Reflecting on his early days in the Kastler-Brossel Lab, he said, “Brossel never pressured us to conduct ‘useful’ experiments.”

Wu Haiteng, a postdoctoral researcher at East China Normal University’s Institute of Quantum Science and Precision Measurement, who also studied in the Kastler-Brossel Lab, shared his experience. “Ph.D. students here have a lot of freedom,” Wu said. “Professors give clear guidance, and for the next four or five years, we are free to pursue what we believe is important. Publishing papers is not a strict requirement for graduation. As long as we contribute to the lab’s work, the professors consider it a success.”

Haroche also views “deglobalization” as a growing challenge for science. “We should protect the global nature of science, and scientists in the West and China must maintain exchanges,” he said.

Haroche interacts with participants at the 2024 WLA Forum. (Photo provided to People’s Daily)

Life Beyond Quantum Physics

Since childhood, Haroche and his brothers have read together, visited museums, and discussed topics ranging from ancient history and literature to modern politics.

He saw strong connections between science and the humanities. “Science and the arts both pursue something mysterious and fascinating,” he said. “Historically, periods of scientific progress thrived on the exchange of ideas with artists, philosophers, and sociologists.” Many great scientists, such as Einstein and Descartes, were also deeply engaged with the humanities, and Haroche was no exception.

“I often watch music performances. I like Italian painters from the 15th to 17th centuries, like Titian and Michelangelo. Some of my friends are musicians, and I listen to music to unwind,” he said.

Haroche is interviewed by People’s Daily at the WLA Forum. (Photo: Zhou Haoyu)

At the 2020 WLA Forum, Haroche said that “a good scientist should also understand the humanities.” He argued that academic freedom has fueled critical thinking and creativity from the Renaissance to the quantum era, making science a transcendent, global pursuit.

When he learned that his interviewers were from humanities programs, he showed a keen interest in the curriculum structure in Chinese universities. Leaning forward in his chair, he asked, “Do your studies include courses in basic sciences or applied technology?” When he received an affirmative answer, he settled back with a nod, saying, “That’s as it should be.”